- Home

- Marie Nizet

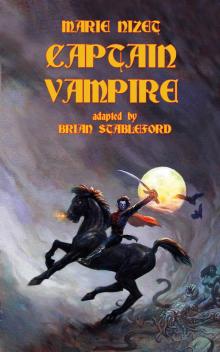

Captain Vampire

Captain Vampire Read online

Captain Vampire

by

Marie Nizet

translated, annotated and introduced by

Brian Stableford

A Black Coat Press Book

Introduction

Marie Nizet’s Le Capitaine Vampire, originally published in Paris in 1879 by Auguste Ghio, was lost to sight for more than a century. The Bibliothèque Nationale has no copy, nor has the British Library or the Library of Congress. The book was rediscovered by Radu Florescu, a Rumanian scholar who had made something of a specialty out of researching the historical background of Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) and the Voivode on which the eponymous character was modeled, Vlad Dragul, alias the Impaler. One of Florescu’s successors, Matei Cazacu, appended a reprint of Nizet’s novella to his own compound biography (in French) of the historical and literary figures, Dracula (2004), and included a chapter in his commentary speculating about its possible influence on Stoker.

Cazacu’s research into Marie Nizet’s background revealed that she was born in Brussels on January 18, 1859–which means that she had not long turned 20 when Le Capitaine Vampire was published, presumably having written it at 19. Her father, François-Joseph Nizet (1829-1899), was a lawyer whose numerous political pamphlets, of a fervently patriotic stripe, had won him an appointment as the joint curator of the Bibliothèque Royale; while occupying that position, he published various scholarly works in the fields of bibliography and history. Marie’s younger brother, Henri (1863-1925), also embarked on a literary career as a journalist and novelist.

Although Henri remained in Brussels to pursue his studies, Marie went to Paris to complete her education, where she cultivated a strong interest in Rumanian culture and folklore. In 1878, she published a volume of poetry entitled România; Cazacu observes that many of its inclusions are based on native ballads celebrating the continual wars of independence fought against the Turks of the Ottoman Empire, but that her political commentary takes even greater offence at the treatment of Rumania by the “great powers” whose international conferences strove to settle “the Turkish question” in the 1870s–with the eventual result that Rumania became a pawn of Russian imperial ambitions in the Russo-Turkish war of 1877-78, which forms the historical background of the story told in Le Capitaine Vampire.

Marie Nizet never visited Rumania; her knowledge of the country and its predicament was very largely based on information provided by two close friends: Euphrosyna and Virgilia Radulescu, the daughters of the late writer and fervently anti-Russian political agitator Ion Heliade Radulescu (1802-1872). Radulescu was considered to be the foremost 19th-century representative of Rumanian culture; he founded and edited the first Rumanian newspaper and played a leading role in the 1848 “Muntenian revolution,” becoming a member of the provisional government set up thereafter. He was well-known in France, and contributed articles to many of the leading French newspapers.

For Marie, under the spell of Euphrosyna and Virgilia, Rumania became part of that Parisian land of dreams called “the Orient,” to which many Parisian writers made imaginary pilgrimages, if not actual ones. She seems to have found it very easy to empathize with her friends’ patriotism, and their indignation at the Tsar’s abuse of his Rumanian allies. The centerpiece of her story–the fulcrum around which everything else is organized–is an account of the storming of the Gravitza redoubt on September 11, 1877, when several regiments of the Rumanian army were ordered by their Russian commander-in-chief to lead a dangerous assault that had a tremendous cost in human lives.

Cazacu, whose only focus of interest is the character of “Captain Vampire” himself, suggests that the inspiration for the novella might have come from one of Ion Heliade Radulescu’s poems, Zburàtoral, which describes a young girl’s sexual awakening in response to the visitation of an incubus. Nizet’s novella has a very different theme, though, and the most obvious literary influences manifest in the novella are two of Charles Perrault’s didactic fairy tales, known in English as “Cinderella” and “Little Red Riding-Hood.”

In studiously echoing these moral tales, Nizet is not attempting to produce an “art fairy tale” of the kind beloved by some Romantic writers, but quite the reverse; she refers to the stories primarily to mock and deny them, calling attention by contrast to the fact that real life is not at all like a fairy tale. Although its plot has supernatural elements, and its antagonist is manifestly demonic, the eponymous monster is part of a more elaborate pattern of symbolism whose purpose is to bring out the horror of actual events. First and foremost, and in its very essence, Le Capitaine Vampire is a war story, and a very striking one. In its method and tone alike, it was way ahead of its time, and the principal reason for the book’s rapid descent into obscurity might well have been its discomfitingly cynical treatment of the ugliness of warfare–a treatment that must have seemed more than slightly shocking as the composition of a young woman of 19.

We are now so accustomed to reading fiction of the “war is hell” variety, including fiction dealing with contemporary wars, that it is easy to forget how recent a literary product it is. War is surprisingly inconspicuous among the topics of early literature; such battles as are featured in literature before 1800–the siege of Troy in Homer’s Iliad, the First Crusade in Gerusalemme Liberata (1580) by Torquato Tasso and the battle of Agincourt in William Shakespeare’s Henry V (1600) are among the most famous examples–were invariably distanced by history to the extent of having become legendary. Countless writers active between the era of Geoffrey Chaucer’s knight and the American Revolution lived through wars, but almost none offered any substantial account of them; the conventional manner of representing past battles was to present them as arenas of glorious heroism.

Hans von Grimmelshausen was probably the first writer to incorporate the legacy of his own experience–he was press-ganged into the Thirty Years War at the age of 13–into a major literary work, the satirical novel Simplicissimus (1669; tr. 1912). However, Grimmelshausen’s demolition by mockery of the guiding myths of “aristocratic warfare”–duty, chivalry and heroism–stood virtually alone for more than a century. Similar analyses only began to emerge in numbers when the era of “political warfare” began as the slow spread of democratic responsibility began to engage whole populations–tacitly, at least–in matters of diplomatic propriety. That was the context in which Napoleon Bonaparte became a legend in his own lifetime, but the most notable dramatic account of the battle of Waterloo (1815) was not written until Stendhal produced La Chartreuse de Parme (The Charterhouse of Parma; 1839) a generation later.

The business and representation of war were irrevocably altered by the Crimean War of 1854-56, which was the first to be extensively reported in the press. The highly critical running commentary provided by the London Times mobilized popular opinion so successfully that the public became intoxicated by its newly-discovered right of censure and laid virtual siege to Parliament, while the military complained bitterly that all its secrets were being given away. The combatants in the Crimea included Leo Tolstoy, but he preferred to look back at a more distanced conflict in compiling his massive quasi-sociological study of War and Peace (1863-69).

The American Civil War of 1861-65 was reported even more conscientiously than the Crimean War, with the additional luxury of illustrative photography. The reportage of the Crimean and American Civil Wars–especially the latter–provided the imaginative kindling for the genre of contemporary war poetry, the vast majority of the works collected thereafter being written by civilians reacting to the news, but prose fiction featuring their major battles was more belated.

The Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 made a brutal impact on the many writers who lived in Paris; they had to suffer the siege of the city and the consequent bloody

reign of the Commune. Even that experience, however, did not call forth a swift response in the form of substantial works of prose fiction set against the background of the war. The sharp example set by Bismarck’s relentlessly efficient army did give prompt birth to a significant subgenre of future war stories, pioneered in Britain by George T. Chesney’s ingeniously alarmist The Battle of Dorking, but most of the early works comprising that genre were jingoistic celebrations of potential conquest rather than reflections on the potential horrors of future warfare.

In 1879, therefore, the subgenre of contemporary war fiction hardly existed, and the subgenre of contemporary anti-war fiction did not exist at all. There was nothing with which to compare Marie Nizet’s Le Capitaine Vampire in its own day, and even when the Great War of 1914-18–the first in which press coverage became a heavily-censored vehicle of propaganda–began to generate reactive literary works on a massive scale, very little was produced that used techniques of symbolic exaggeration similar to those that Nizet found convenient.

As a war story therefore, Le Capitaine Vampire–which deals with a key event that had taken place less than two years before its publication–may be reckoned to have languished without the remotest parallel for at least half a century. Seen in that light, there is a certain irony in the fact that it has only begun to attract attention again because of its status as a vampire story, and its possible influence on the most famous vampire novel of all. Given that this is the case, however, the issue must be squarely addressed.

The possibility of the novella’s possible influence on Bram Stoker cannot be sensibly discussed without extensive reference to its plot, so that sort of speculation is best left to an afterword, where it cannot spoil the reader’s enjoyment in advance. It is, however, appropriate to offer a brief consideration here of the earlier history of French vampire fiction, in order to identify the groundwork on which Nizet might have been able to draw in selecting and shaping her key motif.

Cazacu observes that Marie Nizet’s text does not employ any of the Rumanian words associated with vampire folklore–he lists strigoï, vârcolac, moroi and nosferatu–but only the word “vampire” itself. He notes that the word is of Slavic origin, but that is unlikely to be of any significance; by 1879 it had become commonplace in French parlance and it is with its French meaning that Nizet concerns herself. Indeed, she makes no reference at all to vampire folklore, although almost everyone else who wrote 19th-century French fiction featuring vampires seems to have had some knowledge of the contents of Dom Augustin Calmet’s classic treatise on the subject, first published in 1746, even if that information had been filtered through the popular collection Infernaliana (1822; belatedly attributed, perhaps dubiously, to Charles Nodier).

Infernaliana’s selective recycling of Calmet’s “case studies” includes a substantial chapter on “Vampires de Hongrie,” which is presumably responsible for the fact that most 19th-century French vampire novels feature Hungarian vampires rather than Rumanian ones. Nizet shows not the slightest evidence of familiarity with Infernaliana or its source, or of having taken any notice of such elements in later texts shaped under its influence.

There were, however, other significant inputs to the development of the French literary mythology of the vampire, of which the most important was John Polidori’s novelette The Vampyre (1819), which was rapidly translated into French. The Vampyre gave rise to several imitative works, including two successful dramatic adaptations, both entitled Le Vampire and both produced at the Porte-Saint-Martin theatre, in 1820 (a version adapted by Achille Jouffroy d’Abbans, Jean-Toussaint Merle and Charles Nodier) and 1851 (a version further adapted by Alexandre Dumas and Auguste Maquet).1

Although it is highly unlikely that Nizet had seen the play performed, she might well have read the script of Dumas’ version in the 1876 edition of his collected plays, just as she might easily have read a translation of Polidori’s original. Both texts feature male vampires, as Nizet’s does, but this was relatively rare in early 19th-century French literature; the texts she could have found even more easily–including Théophile Gautier’s nouvelle “La morte amoureuse” (1836; tr. as “Clarimonde” or “The Dead Leman”) and two poems from Charles Baudelaire’s Les fleurs du mal (1857), “Le vampire” and “Les métamorphoses du vampire,” employ the word in a psychosexual context with respect to female temptresses (although Baudelaire’s use of the masculine pronoun suggests that it is male lust rather than the female object of desire that he is characterizing as vampiric).

The only other text Nizet is likely to have run across which features a male vampire is Paul Féval’s La ville vampire (1867 as a serial),2 whose first book version was issued in 1875 and must still have been available for purchase when she arrived in Paris. Although Féval’s novella is a historical comedy parodying the excesses of English Gothic fiction, it does have two features that are found nowhere else prior to 1879 and which are reproduced in Le Capitaine Vampire: the vampire’s ability to be in two places at once, and an extensive exercise in symbolism that makes vampirism a lurid exaggeration of various sorts of human depredation, including those associated with warfare. The former is trivial, but the latter may be more significant.

The word “vampire” was extensively used in a metaphorical sense before 1879. Baudelaire’s use of it as a symbol of the male response to female sexuality reflected a trend that eventually gave rise to the American use of the term “vamp” as a description of predatory women–especially those featured in the cinema–but the more frequent and lurid application was in socialist rhetoric that represented capitalists as “bloodsucking” predators. Karl Marx’s Das Kapital (1869; French tr. 1873; English tr. as Capital) makes continual reference to proprietors as “vampires.”

Nizet gives no clear evidence of being a revolutionary socialist, in spite of being fervently anti-aristocratic and pro-proletarian, but Ion Heliade Radulescu had played a leading role in the local version of the wave of revolutions that swept Europe in 1848, and his daughters would certainly have been familiar with contemporary revolutionary rhetoric. This influence could have combined with that of La ville vampire to make it seem very appropriate to Nizet to symbolize the ultimate Russian bogey-man as an aristocratic vampire.

Before reading Le Capitaine Vampire the reader might find it useful to know a little more about the historical background of the story. The Ottoman Empire had been in decline throughout the 19th century, and its grip on its European components was seriously weakened once the revolutionary movements of 1848 had kick-started nationalistic independence movements in many of the relevant territories–especially those which had substantial Christian populations. Freedom of religious observation became a key demand of many of these movements, and licensed the intrusion of Western European nations, which could pose as champions of Christendom in lending support to anti-Ottoman activity. Whatever quantum of sincerity here may have been in the governments of France and Britain taking this line, however, there is no doubt that the Tsar of Russia was entirely concerned with the possibility of extending his own empire at the expense of the ailing Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires.

Unlike the far-flung empires of France and Britain, the Russian Empire had always been geographically connected, expanding by annexation rather than by maritime adventurism. In this respect, the youngest and most aggressive imperial power in Europe, Otto von Bismarck’s Germany, was something of a hybrid, but it too had political aspirations in Eastern Europe, which required delicate negotiations with the Russians regarding the pickings that might soon become available.

The Treaty of Paris, which ended the Crimean War in 1856, guaranteed the integrity of Turkey, which kept control of the provinces south of the Danube river. Russia, having been defeated, ceded Bessarabia, and the Black Sea was established as neutral. This accord did not last long, though; the Black Sea clauses were repudiated by a conference of the great powers that took place in London in March 1871, shortly after the armistice that brought the Franco-Prussi

an War to an end and shortly before the Peace of Frankfurt, by which France ceded Alsace-Lorraine to Germany. In September 1872, the Emperors of Germany, Austro-Hungary and Russia met in Berlin to negotiate an entente, which bound them to set aside their own disputes in order to present a united front against the Turks. This became a formal alliance in October 1873.

These political shifts greatly encouraged the revolutionary movements in the Ottoman sphere of influence, and the Sultan of Turkey was forced to promise reforms in December 1873. The Ottoman Empire was in desperate straits economically, high-interest bonds it had issued in order to raise revenues from western Europe having collapsed in value.3 The promised reforms did not take place–not, at least, rapidly enough to satisfy the rebels–and the Turks became increasingly repressive; in one notorious incident in March 1876, their troops slaughtered Bulgarians on a massive scale.

This prompted the German/Russian/Austro-Hungarian alliance to issue the Berlin Memorandum of May 13, demanding that the Turks call a cease-fire and return to the path of reform (the British prime minister, Benjamin Disraeli, was invited to sign it, but declined–he too was apprehensive of the alliance). The Sultan of Turkey, Abdul Aziz, was assassinated on May 30, and several more members of the Ottoman government were murdered in June. On June 30, Serbian nationalists declared war on Turkey.

Abdul Aziz’s successor, Murad V, was deposed on August 31, allegedly on the grounds of insanity. On October 31, the Turks agreed to an armistice in response to a Russian ultimatum, but Russia immediately began preparing to go to war against them. The Constantinople Conference in December ended in the proclamation of an Ottoman Constitution, which established parliamentary government and guaranteed freedom of worship, but the revolutionary tide had become unstoppable.

Captain Vampire

Captain Vampire